Mohamed Hachaichi

Ph.D. in circular urban metabolism & climate change, AI-driven enthusiast, and passionate about Ecological Transition.

Green Horizons: Navigating COP 28’s Carbon Footprint – Emphasis on Africa and the Global South

Hachaichi Mohamed

Abstract

With each additional COP conference, there is a growing chorus of criticism due to the high carbon footprint associated with the event, mostly due to the intensive amount of international air travel. There has also been a growing chorus of voices raising the related question as to whether COP conferences can become virtual to play a greater leadership role in the reduction of carbon emissions and serve as a good role model for what it is advocating to the rest of the world. COVID19 demonstrated that it was possible for billions of people to adapt and rapidly change behavior from physical face-to-face meetings to virtual online ones. Even after COVID19 was over, many meetings that have migrated permanently to online. In this study, we consider the feasibility of migrating COP from a currently high to a low carbon emission event, mainly by minimizing the amount of air travel and cutting indirect carbon emissions. The study is framed as an optimization problem, a tradeoff between the carbon emissions of tens of thousands of long distance flights to one global COP destination and the carbon emissions of many shorter trips to an increased number of regional destinations.

Keywords

Carbon emissions: geography of carbon; COP28

The COPs, or Conference of the Parties, are annual meetings where UNFCCC member countries gather to address climate change collaboratively (Werksman, 1996). These conferences serve as vital forums for global cooperation, aiming to formulate and implement measures that mitigate climate change impacts. The COPs set targets, guidelines, and agreements to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote sustainable development, and foster international collaboration (Mayer, 2018). Through these negotiations, COPs play a pivotal role in shaping the collective response to the urgent challenge of climate change.

From the inaugural COP1 in Berlin to the latest COP28 in Dubai, these events have consistently drawn participants from across the globe, underscoring the international significance and widespread engagement in addressing the critical issue of climate change. During the COP28 in Dubai was highlighted by the slogan “Beginning of the End” of the Fossil Fuel Era. To discuss options and unlock novel trajectories, over 97,000 individuals physically attend the Conference of the Parties (COP) in Dubai (McSweeney, 2023). This has sparked criticism because of the significant carbon footprint linked to the event, primarily stemming from the extensive use of international air travel.

COP 28 marked a significant milestone as the inaugural Conference of the Parties to systematically collect open data encompassing all conference attendees, including details on their respective affiliations and countries of origin. The availability of this open dataset is pivotal for the conduct of the present study. The invited participants encompass diverse roles such as directors, advisors, ministers, experts, officials, officers, managers, ambassadors, presidents, CEOs, and members of parliaments, hailing from various countries. Notably, there exists a substantial variation in function titles across different nations, primarily attributable to the distinct climate challenges faced by countries globally.

To calculate the virtual carbon emissions associated with the transportation of individuals to the recent COP28 in Dubai, three essential types of databases are required. Firstly, a roster of attendees, comprising individuals who participated in the COP, was sourced from the United Nations’ Climate Change (UNFCCC) (UNFCCC, 2023). The second database entails information on the distances between international airports, specifically the airports in the attendees’ countries of origin and the final destination, Dubai International Airport, in this analysis. The distance between two airports is determined utilizing the Haversine distance method, as outlined in Equation 01. Lastly, emissions factors for airplanes were obtained from the French database of emissions factors provided by the French Ministry of Ecological Transition.

Equation (01):

$D(x,y) = 2arcsin[sin^2((x_{\text{lat}}-y_{\text{lat}})/2) + cos(x_{\text{lat}}) \cdot cos(y_{\text{lat}}) \cdot sin^2((x_{\text{lon}}-y_{\text{lon}})/2)]] $

To quantify the virtual carbon emissions resulting from COP 28 hosted in Dubai, the transport distance (expressed in kilometers) between the departure airports of attendees traveling to COP 28 from diverse countries and the designated destination airport in the city of Dubai (Dubai International Airport) was calculated as outlined in Equation 02:

Equation (02):

$Carbon Footprint = Distance * emissions factor * traveled distance$

Where: D: is the distance between the origin country’s airport and the destination airport in km. EF: is the emissions factor for aircraft in kg CO2-eq/ km the value is equal to 1.20 kg CO2eq /km. The carbon footprint is afterwards multiplied by two to capture both the total carbon emissions emitted from departure and arrival. For the initial database involving individuals from various countries attending COP 28 in Dubai, several preprocessing steps were necessary. Firstly, each origin country needed to be assigned a specific airport. In this study, the selection was based on choosing the largest international airport situated within the capital city of each country. Nevertheless, exceptions were essential. For instance, European Union attendees were assigned to Belgium (Brussels Airport) due to the EU headquarters being located there. For Liechtenstein, lacking its own airport, we opted for the nearest and most frequently used airport, Zurich’s airport. Similarly, for Monaco, we assumed that the staff traveled via the French airport of Nice Côte d’Azur Airport (France). Additionally, staff from the Holy See were assigned to Rome’s Leonardo da Vinci–Fiumicino Airport (Italy). These assumptions were imperative for calculating the distance between the origin airport of each country and the destination airport (Dubai International Airport).

In this analysis, it is assumed that all COP28 attendees traveled on an Airbus A340-600 aircraft with 320 seats. The number of attendees from each country is subsequently divided by 320. In instances where the resulting quotient exceeds 1, the number is rounded, and then multiplied by the carbon emissions associated with the aircraft. This procedure ensures the estimation of the total number of aircraft mobilized for transporting individuals from the origin country’s airport to Dubai International Airport.

The attendance data for COP28 in Dubai reveals a diverse representation from different continents (Figure 01), signifying global engagement in climate-related discussions. The highest attendance is observed from Africa, with 10,010 participants, indicative of a substantial commitment to environmental issues within the African continent. The Americas show a moderate level of representation with 2,938 attendees, suggesting varied levels of awareness or participation across North and South America. Asia exhibits a significant presence at COP28, boasting 7,372 attendees, likely driven by the diverse array of countries in the continent actively engaging in climate-related dialogues. Europe, with 3,281 participants, demonstrates a noteworthy contribution to the conference, reflecting the region’s active involvement in addressing climate change. Oceania, with the lowest attendance at 887, indicates a smaller representation possibly influenced by the region’s smaller population and geographical size. In conclusion, the attendance distribution underscores the global interest and commitment to addressing climate change, with regional disparities reflecting nuanced factors influencing participation in such crucial international forums.

Figure 01: Number of physical attendues to COP 28 in Dubai.

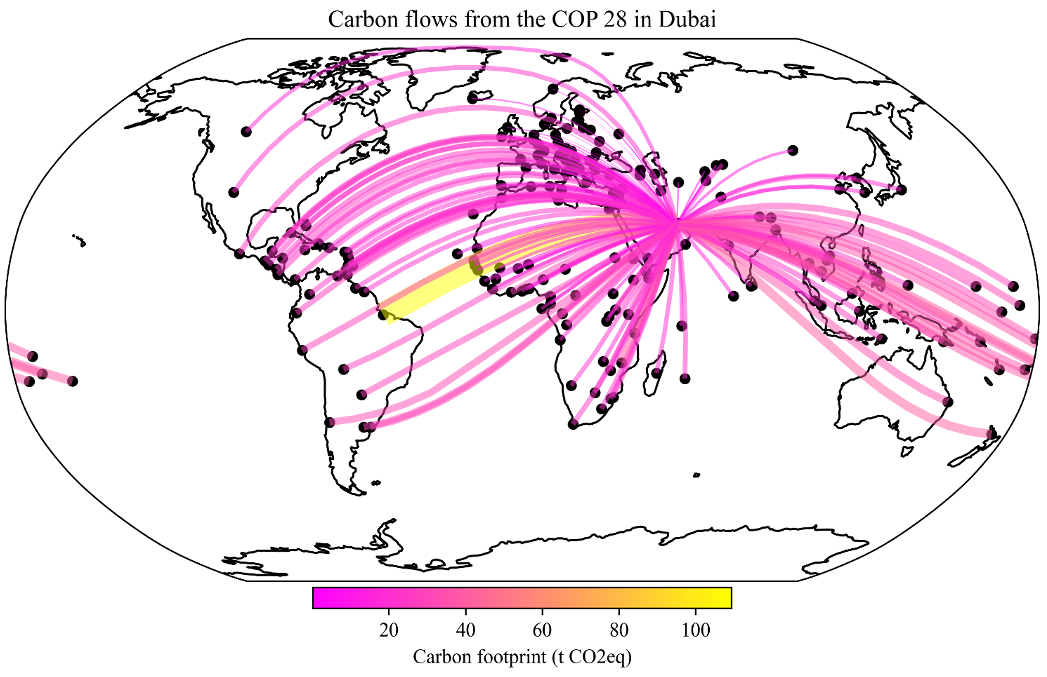

During COP28 in Dubai, the substantial influx of participants resulted in a noteworthy environmental impact, with a total carbon footprint of 3,183.81 metric tons of CO2eq solely attributed to the international travel to the event. These emissions predominantly originated from air travel, specifically the combustion of aviation fuel during flights, highlighting the significant contribution of transportation to the overall carbon footprint of the conference. As global leaders gathered to address climate concerns, the event underscored the paradoxical challenge of mitigating emissions associated with the very means by which individuals convene to address environmental issues.

The analysis of each country’s responsibility (Figure 02) in terms of their total carbon footprint, factoring in the distance and the number of participants, reveals the following top contributors: Brazil: With a total carbon footprint of approximately 109.34 metric tons of CO2eq, Brazil leads the list. Despite having a relatively low carbon footprint per participant, Brazil’s significant total carbon footprint can be attributed to the high number of participants and the considerable distance to Dubai. India: India has a total carbon footprint of about 40.73 metric tons of CO2eq. Its carbon footprint per participant is lower than Brazil’s, but the total contribution is substantial due to the number of participants and distance. New Zealand: New Zealand, despite having fewer participants, has a high carbon footprint per participant, contributing to a total carbon footprint of around 40.66 metric tons of CO2eq. This high per-participant footprint is likely due to the long distance to Dubai. Cook Islands and Tonga: These countries have significantly high carbon footprints per participant, contributing to total footprints of approximately 38.85 and 38.05 metric tons of CO2eq, respectively. The high per-participant footprint is again influenced by the great distances to Dubai.

When reducing the scale of the analysis, the data by region and sub-region displayed that: By Region: Africa is the top contributor with a total carbon footprint of approximately 932.95 metric tons of CO2eq. Americas closely follows with about 905.24 metric tons of CO2eq. Asia, Oceania, and Europe follow with total carbon footprints of 653.04, 543.36, and 149.23 metric tons of CO2eq, respectively. By Sub-Region: Sub-Saharan Africa leads with a total carbon footprint of around 880.01 metric tons of CO2eq. Latin America and the Caribbean are next with approximately 865.94 metric tons of CO2eq. Other significant contributors include South-eastern Asia, Polynesia, and Western Asia. These findings highlight the diverse contributions to the carbon footprint from various countries and regions, with distance and participant numbers being key factors.

These findings highlight the varying degrees of responsibility in terms of carbon footprint from both a country-specific and a geographical perspective. This analysis can be instrumental in understanding and addressing the environmental impact of such international events.

Figure 02: Carbon emissions generated by COP 28 in Dubai.

Figure 02: Carbon emissions generated by COP 28 in Dubai.

The African delegation was responsible for 29.3% of the total air transport carbon emissions during the COP28. Africans from various countries have converged at COP28 in Dubai with a shared commitment to addressing climate change on the continent, both in terms of mitigation and adaptation measures. The primary motivation stems from the urgent need to mitigate future carbon emissions (Hachaichi & Baouni, 2021), find sustainable solutions for African economies and cities (Cobbinah & Finn, 2023) and reduce overall socioeconomic risks (Ayanlade et al., 2023). With the continent grappling with severe drought episodes impacting water security (Taing et al., 2019), agriculture (Dinar et al., 2012), and consequently, food security (Hachaichi & Egieya, 2023), attendees are actively seeking international cooperation and innovative strategies to adapt to the adverse effects of climate change. This collaborative effort aims to foster a resilient Africa that can navigate the challenges posed by global warming, ensure sustainable development while mitigating current and explore novel trajectories to control future carbon footprints.

The COP28 to focus on delivering real results for Global South, Dr. Sultan Al Jaber, the President-Designate of COP28, presented a virtual address during a meeting of Ministers and High Authorities of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation of G77 + China, emphasizing the importance of sustainable, inclusive, and resilient development. The G77 nations, representing 80 percent of the global population, serve as a crucial platform for the Global South to articulate a unified stance on the pressing issue of climate change. Dr. Al Jaber underscored the heightened significance of the Global South’s voice, particularly as the region bears the brunt of climate impacts. COP28’s agenda aims to formulate an ambitious and practical plan of action tailored to address the specific needs of the Global South. The conference pledges to expedite a just energy transition, marked by a threefold increase in renewables, a twofold rise in hydrogen production, enhanced energy efficiency, and a phasedown of fossil fuel usage. Dr. Al Jaber stressed the imperative of preserving energy affordability, accessibility, and security while sustaining socio-economic development. Access to modern energy is key to unlock sustainable development in Africa (Belmin et al., 2022). The outcome of COP28 is anticipated to be a comprehensive plan of action reinvigorating progress across all facets of climate action, encompassing mitigation, adaptation, finance, and addressing loss and damage (COP28, 2023).

The discussions at COP28 provide a platform for African nations to share experiences, pool resources as finance resources will need to be doubled to reach $40 billion in order to implement and deploy a truly global early warning system, and negotiate initiatives that not only reduce emissions but also build adaptive capacities, ultimately securing a more sustainable and climate-resilient future for the continent. The database is provided via the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/10607086

References

Ayanlade, A., Smucker, T. A., Nyasimi, M., Sterly, H., Weldemariam, L. F., & Simpson, N. P. (2023). Complex climate change risk and emerging directions for vulnerability research in Africa. Climate Risk Management, 40, 100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2023.100497

Belmin, C., Hoffmann, R., Pichler, P.-P., & Weisz, H. (2022). Fertility transition powered by women’s access to electricity and modern cooking fuels. Nature Sustainability, 5(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00830-3

Cobbinah, P. B., & Finn, B. M. (2023). Planning and Climate Change in African Cities: Informal Urbanization and ‘Just’ Urban Transformations. Journal of Planning Literature, 38(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122221128762

COP28. (2023). COP28 to focus on delivering real results for Global South. https://www.prnewswire.com/in/news-releases/cop28-to-focus-on-delivering-real-results-for-global-south-301869895.html

Dinar, A., Hassan, R., Mendelsohn, R., Benhin, J., & al, et. (2012). Climate Change and Agriculture in Africa: Impact Assessment and Adaptation Strategies. Routledge.

Hachaichi, M., & Baouni, T. (2021). Virtual carbon emissions in the big cities of middle-income countries. Urban Climate, 40, 100986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100986

Hachaichi, M., & Egieya, J. (2023). Water-Food-Energy Nexus in Global Cities: Addressing Complex Urban Interdependencies. Water Resources Management, 37(4), 1811–1825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-023-03455-7

Mayer, B. (Ed.). (2018). The UNFCCC Regime, from Rio to Paris. In The International Law on Climate Change (pp. 33–50). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108304368.003

McSweeney, R. (2023, December 1). Analysis: Which countries have sent the most delegates to COP28? Carbon Brief. https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-which-countries-have-sent-the-most-delegates-to-cop28/

Taing, L., Chang, C. C., Pan, S., & Armitage, N. P. (2019). Towards a water secure future: Reflections on Cape Town’s Day Zero crisis. Urban Water Journal, 16(7), 530–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062X.2019.1669190

| UNFCCC. (2023). List of participants | UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/documents/636676 |

Werksman, J. (1996). The Conference of Parties to Environmental Treaties *. In Greening International Institutions. Routledge.

Bio:

Mohamed Hachaichi is a Postdoctoral Researcher affiliated to Pacte Lab at the Grenoble Alpes University, France. He holds a Ph.D. in circular urban metabolism and climate change from the Polytechnic school of Architecture and Urbanism delivered by the laboratory of “Cities, Urbanism and Sustainable Development”. Mohamed works on urban sustainable development and climate change.